The Nave Clerestory

Rowan and His Collaborators

At the right time of day and the right time of year the nave clerestory is awash in rainbows of color. This is no accident. It is the result of the visions of cathedral architect, Philip Frohman, stained-glass artist Rowan LeCompte, the iconographic work of Dean Sayer and Charles Matz, cathedral staff and committees, the funding of generous patrons and the hard work of numerous other artists and craftspeople who had a hand creating the windows that project this glorious light. It would be impossible to tell the whole story here, but we hope to give you a sense of the enormity of the task and people who helped realize the vision.

Philip Frohman – Cathedral Architect

Photo Courtesy Washington National CAthedral

The story must begin with the architecture itself. Cathedral architect Philip Frohman certainly knew that these 18 massive, 15 x 30 foot openings high in the nave walls would have a dramatic effect on the light in the nave. His instructions to young Rowan LeCompte when they first met – Rowan was 16 at the time – give us a clue to his vision. Rowan says that Frohman “wanted stained-glass windows in his buildings to have richness and sparkle.”

The stories to be told in these 18 windows were developed through collaboration between Dean Sayre, scholar Charles Matz and Rowan LeCompte. The basic idea was to begin with Genesis at the west end of the cathedral, following on the creation theme of the West Rose. Then, moving up the nave, the stories would work their way through the Old and New Testaments ending up at the great crossing.

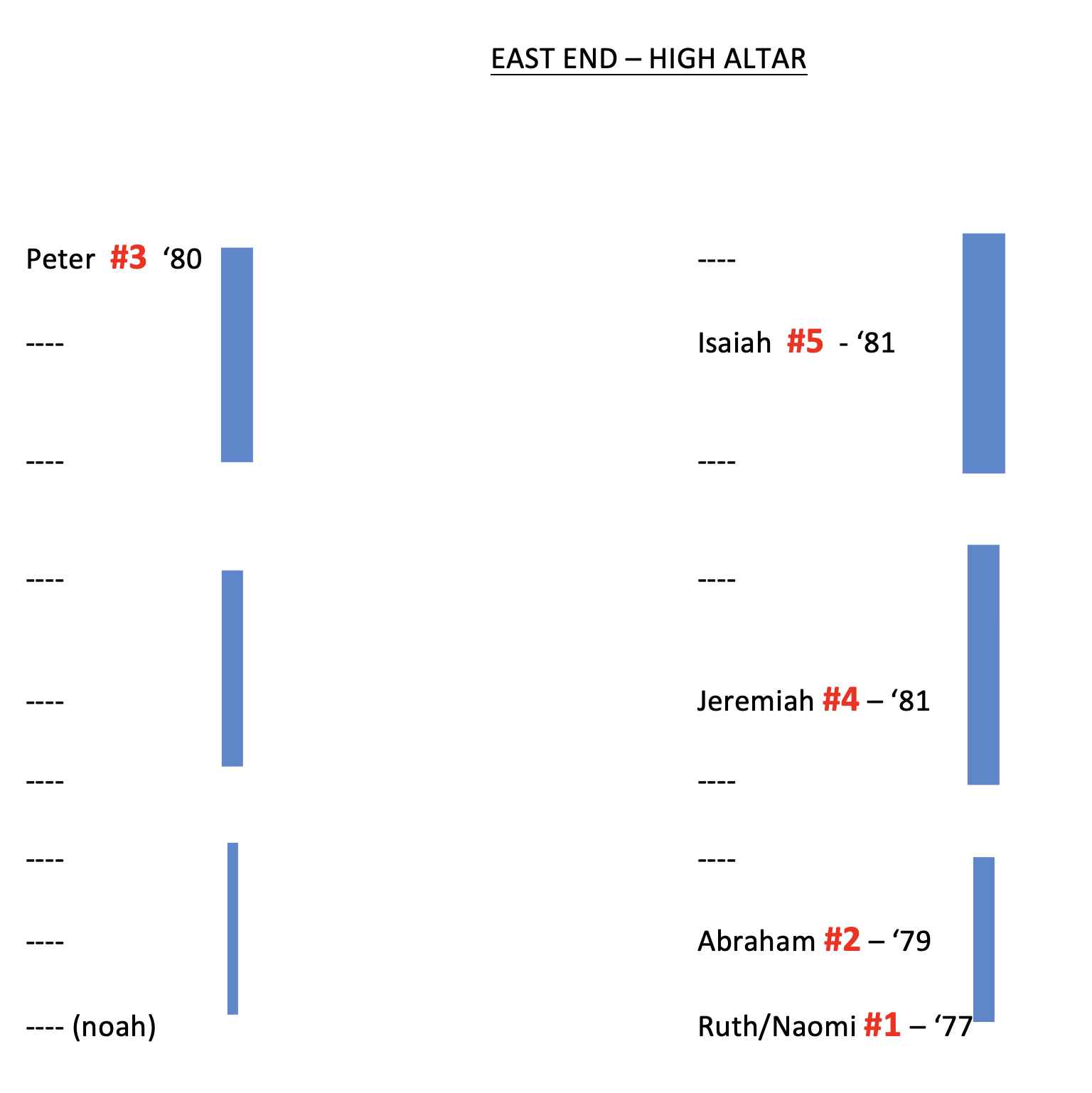

While the nave was to be bathed in light, the choir, on the other side of the crossing was extremely dark by comparison and there was a concern that the brilliant nave would eclipse the activity in the choir. Rowan, working with the building committee and Clerk of the Works Canon Richard Feller, developed a plan to slowly lift the luminosity of the windows as one moved down the nave. They would be darker near the crossing and lighter towards the West End. Cathedral Docent, Doug Gustafson has provided this chart which, “shows the position of the first 5 installed clerestory windows and the 4 degrees of luminosity proposed in 1968 for each section. The wider blue line indicates less luminosity.”

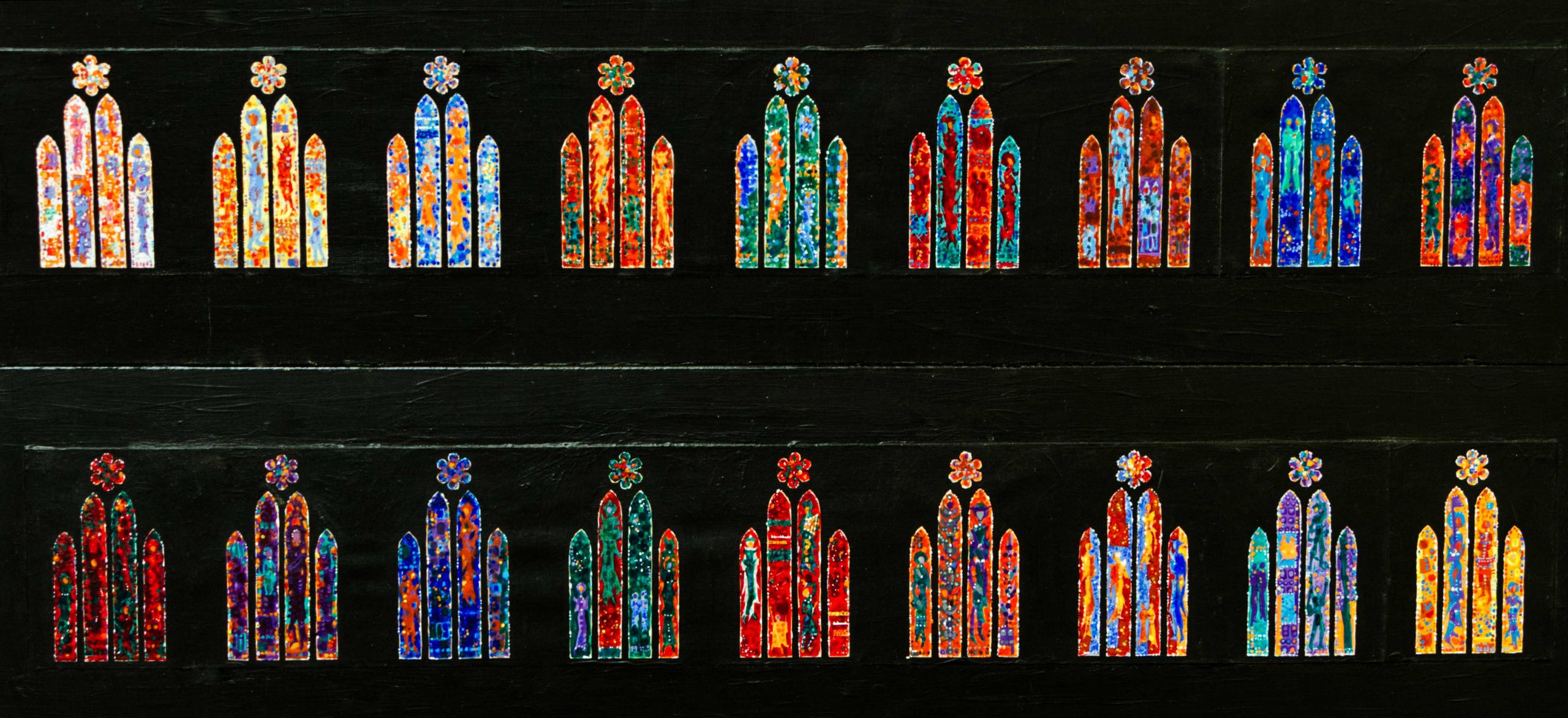

It is important to understand that Rowan was thinking holistically about the nave clerestory and while there were 18 distinct windows, he was imagining one grand artwork that worked hand in hand with the architecture. Here is an early sketch of the clerestory that was made in 1968 by Rowan and his first wife Irene. It clearly shows the shifting in luminosity moving down the nave. Unfortunately, Irene died in 1970 and never saw the nave clerestory finished, but she did have a hand in two clerestory windows closer to the altar as well as many cathedral windows on lower levels of the building.

Nave Luminosity Plan

Nave Sketch 1968

Mary Clerkin Higgins Painting In Her Studio

With a plan in place, work began in 1973 on the first of the clerestory windows, “Isaiah.” This window is on the south side of the building, is the second window towards the west from the crossing, and was to be the darkest of the clerestory windows. This work was interrupted, however, as the cathedral wanted Rowan to focus on the West Rose so it could be completed for the dedication of the cathedral in 1976. Once that was finished Rowan resumed the monumental task of creating the 18 clerestory windows. In this effort he was not alone.

Making a stained glass window is a multi-faceted process that includes designing the image, scaling up the design into full size cartoons, selecting colors and cutting the glass, painting detail on the glass, encasing the glass pieces in lead and installing the window. While Rowan could do all of these things, he knew he would need help on the clerestory. Instead of returning to the Isaiah Window, after the West Rose Rowan began on the Ruth and Naomi window and made it in New York City at the studio of his friend and colleague Melville Greenland. On this window Rowan did the design, cartooning, glass selection and painting and Mel and his studio did the rest. It is interesting to note that at the time Mel had just taken on a young apprentice named Mary Clerkin Higgins. (Mary has recently written a paper about the nave clerestory collaborations, from which we will draw heavily in the coming paragraphs, and she has graciously allowed us to include it on this web site. It is well worth your time and you click on the button to the left to read it.)

Mary says Rowan next did two other windows at Greenland’s studio with the same division of labor. These were Abraham and Isaac and The Calling of Peter. According to Mary, “Rowan was finding that it could take about 2 years per window even when he only did the color selection and painting. With 16 more large windows to make, it could easily take him more than 30 years to complete the nave. He realized he would have to speed up the process by entrusting certain aspects of the work to other artists.”

Over the ensuing years Rowan worked with a variety of collaborators in a variety of ways. These included the well‐known Belgian artist, Benoit Gilsoul, Mel Greenland, Dieter Goldkuhle, Peter Mollica, Richard Avidon, Mary Clerkin Higgins, who became a stained glass master in her own right, and Carl Edwards and his daughter, Caroline Benyon, who made one of the windows in England.

Mary says he worked with different people in different ways. “ With Mel it meant his studio would do all the craft work and Rowan would do everything else. With Dieter it meant Dieter would do the color selection as well as all the craft work. With me, I did the color selection and some of the painting, and then my studio did all the craft work. Richard Avidon, did color selection and painting, but no fabrication, and Peter Mollica who did all of the above.” As you explore the pages in this light you will learn more about who did what on the various windows.

Trying to interpret Rowan’s vision was not always an easy task and did not always go smoothly. With Dieter, for example, Rowan had an enormous level of respect and trust and yet would often have changes to make once Dieter had selected the glass. Yet Dieter had his own vision and his own love of glass and it seemed that whenever Rowan disagreed with a selection Dieter had made, it tore out a little piece of his heart. For Mary, who often did some painting for Rowan, she had to use a lot of intuition to get at what Rowan wanted, but still bring a bit of herself to the project. “As one of the artists who collaborated with Rowan, I found that I had to jump in and solve the problems to the best of my abilities and with my own voice, or the second guessing would have been completely debilitating. All the while respecting his vision. I hoped he would like my color selection when he saw it, but I had to follow my own instincts and give myself the freedom to fully engage, all the while making Rowan’s window, not my own. It’s a complicated situation. As another artist he worked with, Richard Avidon said ‘All I could do was go with my gut’.”

Mary also observes that it is possible to walk down the nave and see the hand of each of the artists that Rowan worked with in the various windows. As you view these windows, for certain celebrate Rowan and his vision, but also remember that this was not a solitary process and see if you can detect the differences that each of these artists/craftspeople brought to the work.

Dieter Goldkuhle, Mary Clerkin Higgins, Rowan LeCompte, Melville Greenland